[go] -- harmonic architecture

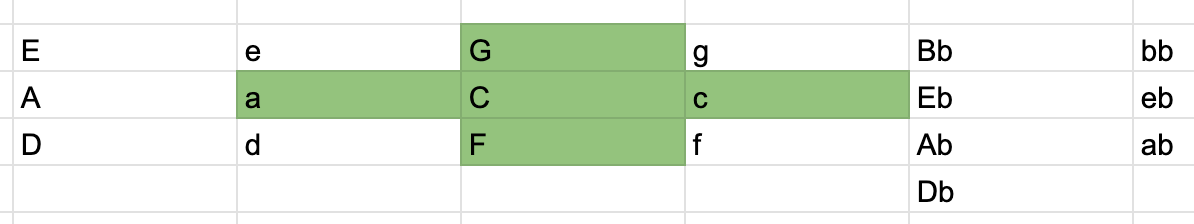

Let us consider the following chart from Chapter 3 of Arnold Schoenberg’s Structural Functions of Harmony. It illustrates the relationship between different harmonic regions, assuming a key center of C. The cells in green indicate the regions closest to this tonal center — the dominant (G), the subdominant (F), the relative minor (a), and the parallel minor (c). Cells further away from this core group represent more distant harmonies.

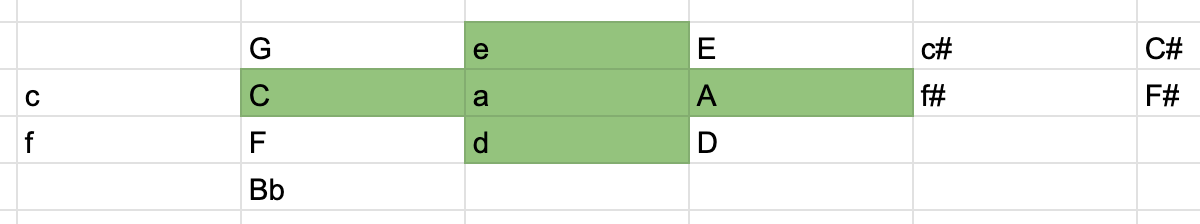

The following table from Chapter 4 assumes a key center of A minor. It is related but distinct from its major cousin.

Although abrupt modulations, like a to G, can and do occur in the literature, composers generally prefer “straight lines”. In other words, instead of moving diagonally from a to G, they usually go from a to C to G. As in geometry, parallel and perpendicular lines dominate.

Musicians often speak of the “harmonic architecture” of a piece. The diagrams above suggest that this phrase may have a more literal meaning. For example, modulation from a to e to E to A to a describes a square. Modulation from C to G to c to C makes a right triangle. What other kinds of shapes have the great masters created with their sounds?